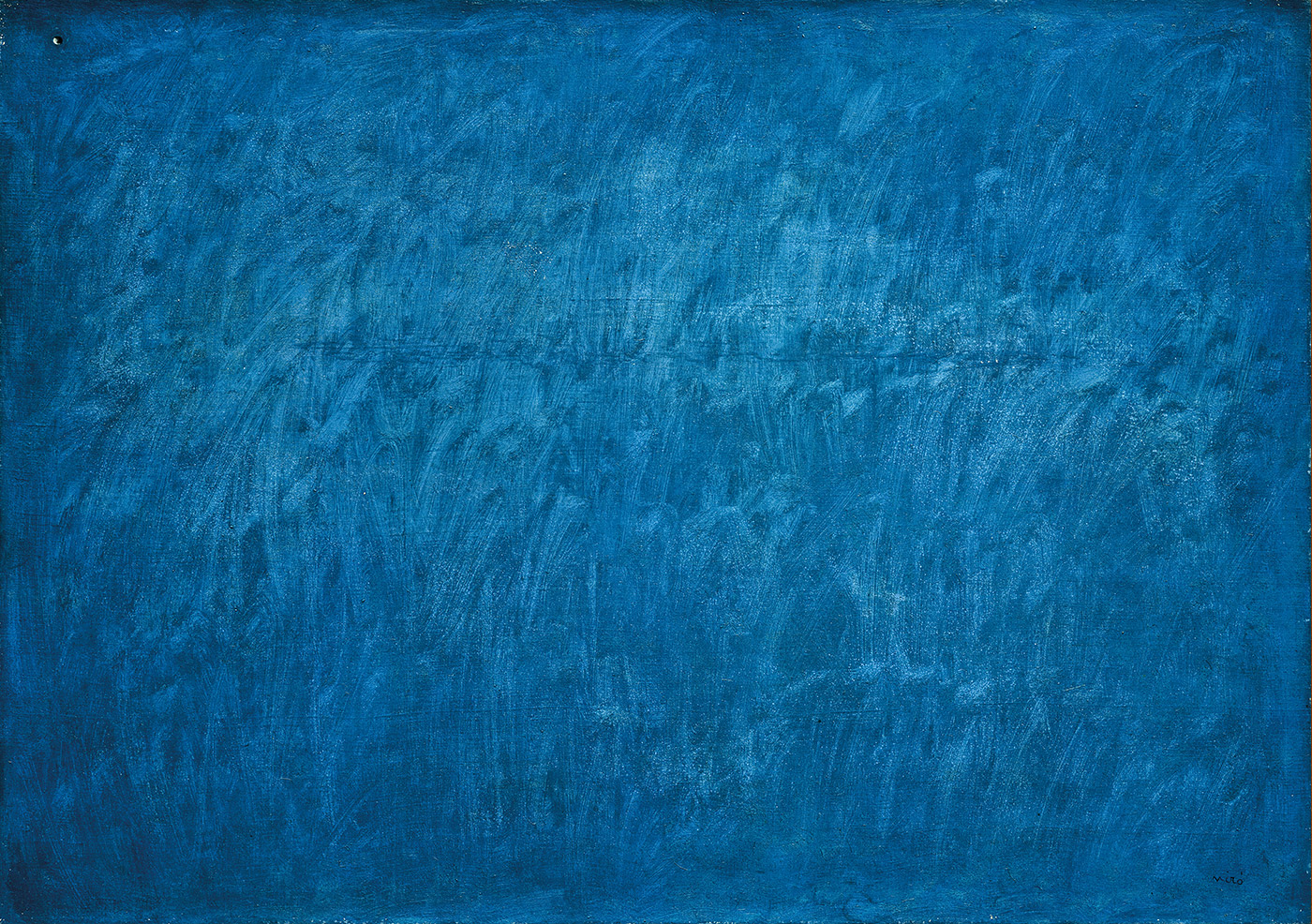

Joan Miró, ‘Blue’ / Schirn Museum

One would think that an artist is an artist. Or rather, that whatever the identity of the artist may be, the work remains just that – the work of an artist. A poem written by anyone is a poem, a piece of music is music and so on. The way all artists work is almost the same, except for some differences, perhaps, in small details. When I sit down at my table to write, I work the same way all writers do, male or female. There are ideas, there are facts, there is the imagination, there is the tool, language. All these come together in creating a story, a poem, a novel, a play, etc. So why, I had to wonder after I became a writer myself, was my work put into the category of ‘women’s writing’? Why was I invariably called a ‘woman writer’? No man was called a ‘man writer’, was he? In fact, of all the arts, only literature stresses the gender of the artist. There even used to be words like ‘poetess’ or ‘authoress’ (thankfully rarely used now) and I found it puzzling that the word poet was not considered suitable to describe everyone who wrote poetry. Very rarely was such gendering done for musicians, dancers, painters, and others. Why then was it necessary for writers? It was not just being identified as a woman writer, it was what these words meant, what they led to: a kind of valuation of the work based entirely on the gender of the writer.

This problem was brought home to me very soon after I began writing. I had read all kinds of books as a child and girl without thinking of the author’s gender. It didn’t matter to me whether the writer was a man or a woman; it was the book that mattered. But when I became a writer, I was almost immediately designated as a ‘woman writer’. It took me some time to understand the implications of this. It meant that my writing belonged to a different category, it meant it was a subspecies called ‘women’s writing’. Men’s writing was the main category and women’s writing was a part of it. Significantly, whenever the work of a woman writer is discussed, the discussion begins with the words ‘Among the women writers’. When I got an award, the write-up on me began with the words, ‘Among the women writers…’. I was incensed and asked the institution giving me the award whether this meant that I had no place in the general pool? That I did not matter in the general pool of writers? There was, of course, no response.

There is no doubt that our vision of the world and our views are shaped by the places and the times we live in, by our families and by the culture surrounding us. Shaped, undoubtedly, also by our gender. Certainly, men and women see the world differently. But the other factors are just as important. All women do not have the same view of the world just because they are women! There is the famous story of the seven blind men touching an elephant and each one seeing a different animal. That we see and portray different worlds adds to the richness of literature; we need these multiple views. A woman’s view, her vision of the world, is just another view, another vision, not an inferior one as it is made out to be. Many women have said this, but the phrase ‘women’s writing’ still survives.

The literary world is littered with chauvinistic ideas, because, sadly, the usual perceptions about women and their place in the world spill over onto the writing. I have been fighting against this ever since I began writing. I have always been saddened that women’s writing is often belittled, marginalised. It has always been believed – in fact, it still is – that women write about emotions, not ideas, women write romantic stories, not about ideologies, they write of small themes, not big issues, women write about families, not about the world and so on. This idea of small and big themes, which came out of male ideas of what is important, was brilliantly confronted and demolished by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own. But the contrary view still continues to be held. Which is why so many men hasten to say, ‘This book is for my wife/ sister/ mother/ daughter.’ Saying, in effect, ‘It is too womanly, not manly enough for me.’

Writing, like all the other arts, is a solitary and independent profession. And risky. There is no guarantee that what I am writing will be ever published, whether it will find readers, whether I will make money. Why write then? Because I want to say something and it matters to me to say it. There is nothing going for me except my belief that what I am saying is worth saying, that I have to say it. A writer needs this belief, this confidence. Only confidence can keep me going. And it is this confidence which is dented when my work is undermined, when I am constantly told that my work is not as important as the work of male authors. That when I write about women, my work remains limited.

Perhaps things are better now than they were when I began writing. I certainly hope that the struggle for gender justice has made an impact on literature as well. Nevertheless, sadly enough, there is still a constant need to convince myself that my writing does matter, and that it is not less important because it is about women’s lives.

Shashi Deshpande

Bangalore

13/ 03/ 2017

Joan Miró, ‘Blue II’ / LANSAC

This is the concluding part of an ICF series of interviews begun on International Working Women’s Day: