Kedarnath Singh was, without doubt, one of India’s finest living poets. The translations of many of his poems into other Indian and foreign languages earned him admirers across the world. His collections, right from Dharati (1945), to the later ones like Abhi, Bilkul Abhi, Zameen Pak Rahee Hai, Yahan Se Dekho, Akal Mein Saras, Uttar-Kabir, Bagh, Tolstoy aur Cycle and Sristi par Pehra (1916-2014) have an internal connectedness and integrity that marks him out as a rare poet of our time.

I began reading him closely when I translated some of his celebrated poems for an anthology of contemporary Hindi poetry into Malayalam. I had begun I editing the anthology with support from the Srikant Verma Fellowship offered by Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal, in 1990.

Our first meeting had also taken place in Bhopal, when I was on my way from the Bhopal airport to Bharat Bhavan. This was in 1980. We stayed together in Bhopal for two weeks when he was translating Shakti Chattopadhyay’s Bengali poems into Hindi. My poems were being translated into Hindi by the young Hindi poet Rajendra Dhodapker.

Soon Kedarnath (I called him Kedar-ji) and I were travelling together to Moscow and Riga along with a few other poets for readings.

He, I thought, was one with his poetry. Like his poems, he was simple, unassuming, rooted, warm, meditative without being sombre, full of memories of his village, and anecdotes about the poets he knew.

He constantly referred to poets whose work he loved, some of whose poems had also influenced his work in different ways: Kalidasa, Surdas, Baudelaire, T S Eliot, W H Auden, Ted Hughes, Pablo Neruda, Yevtushenko, Dylan Thomas, Wislawa Szymborska, Mirza Ghalib, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Jibanananda Das, Muktibodh, and Nirala. Ghalib always entered our conversations. Indeed, there was a lot in common between the ways Ghalib and Kedarnath looked at the world.

Later, we had several occasions to meet and exchange notes as I had moved to Delhi in 1992, and he, too, had made Delhi his home after he joined the famous Jawaharlal Nehru University. He did, of course, make occasional trips to his kin in Banaras and Gorakhpur. His poetry too got “urbanised” to some extent but it retained his concerns for the people, and memories of nature in his village. He had a sustained concern for ordinary folks – peasants, hawkers, workers, and the natural world – animals, birds, trees.

His was more than a city-dweller’s nostalgia for his village. Part of his soul belonged there, and his images were often derived from both the rural landscape and from his workplace. He also translated one of my long poems I had written immediately after I moved to Delhi. We began to gift our books to each other.He released two of my books and wrote a preface to one in Hindi. We read and liked each other’s work as we also found we had a lot in common in terms of sensibility and personal history. What fascinated me, and still does, about Kedarnath’s poetry are the freshness of his images created from day-to-day objects like the spade and the needle, and the loom and the bread, or from natural objects like wood, the sun, birds.

He could de-familiarise the familiar, and, at the same time retain its earthiness.

He could do this even when his poems moved to a surreal realm. His idiom was simple and never laboured. This was a conscious choice; he preferred common Hindustani words over words of Sanskrit origin. He also used simple sentences, or broke up a complex sentence into simple phrases, using a unique strategy — arranging lines that also made punctuation superfluous. This was why a tenderness and warmth saturates most of his poems. His style was deeply contemplative but never overtly philosophical. This kind of subtle distancing helped him to use subtle humour and irony, at times turned upon himself. His poems were also marked by the unconscious intertextuality produced by suggestive allusions. They were completely devoid of loudness, rawness and rancour. This, too, gave a palpable tenderness to his poetry in general.

In my close reading of two of his iconic poems- “Tuta Hua Truck” (The Broken Truck) and “Kudal” (The Spade) I have tried to look at the search for a balanced vision and the rural-urban connect which was always alive in his poetry. Whenever I think of Kedarnath’s poetry, I recall Pablo Neruda’s words:

I have always wanted the hands of people to be seen in my poetry… I have always preferred a poetry where fingerprints could be seen: a poetry of loam where the water can sing, a poetry of bread which everyone could eat.

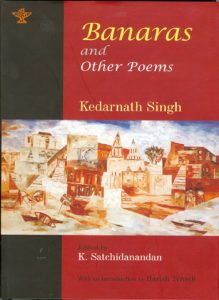

I edited a collection of his poems in English translation, Banaras and Other Poems, some of which I had translated. from the original in Hindi. It was published by the Sahitya Akademi and carried most of Kedarnath’s celebrated poems: “Banaras”, “The Broken Truck”, “An Argument about Horses”, “Recalling 1947”, “On the Eve of the Elections, 1967”, “Between Needle and Thread”; excerpts from “The Tiger”, “The Carpenter and the Bird”, “The Spade”, “Bhojpuri”, “Poetry”, “Hindi”, and many more The last poem was dedicated to me as I had earlier dedicated a sequence from “Madhyamavathy”, a poem written in Bhopal, to him). The preparation of this collection in 2014-15 gave us an excuse for many delightful meetings over cups of wine at the India International Centre where he regaled Harish Trivedi (who wrote a detailed introduction to the collection) and me with his endless, unforgettable, anecdotes around writers, old and new, Indian and foreign, for which he had a special penchant. His eight collections endeared him to the Hindi reading public – the Pragativadis and the Prayogvadis (the Modernists and Progressives) who quarrelled over everything but joined hands when it came to appreciating his unique work as he had combined the political and aesthetic impulses of both. His politics cannot be sought in his statements, but in his poetics. He has, I am told, left enough poems for another collection, sadly his last, that his readers are eagerly looking forward to read. This will, at least, give us the transient, yet exciting illusion, that he is still alive and writing.