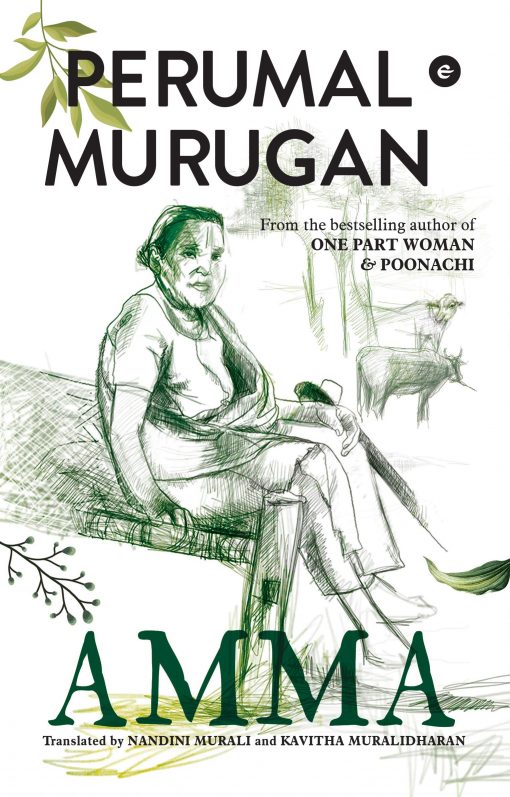

Jointly translated by Nandini Murali and Kavitha Muralidharan, Perumal Murugan’s Amma (“Thondra Thunai” in Tamil), is at the same time both a memoir of Murugan’s mother as well as an account of rural Tamil Nadu’s ‘Kongunadu’ region – both woven into each other. It talks in abundance about the prejudices, moral codes, beliefs, and societal values of the region at the time, making it a multilayered text. The mother is presented as a mix of independence, strength and tenderness, who looked after the household all by herself, while keeping a troublesome husband in control as well. The work is a tribute to a lifetime of hardwork, sincerity and resilience of many similar women in most parts of the country and beyond, whose daily labour simply goes unaccounted for.

The excerpt below is from the chapter “White Sari”, which talks about what Murugan’s Amma was made to face after his father’s death in late 80s. Narrated through a rather touching personal story, the chapter is about the sheer discrimination that was meted out to widowed women of the time.

My father passed away in August 1986. I had just enrolled for my post-graduation then. According to the customs of our caste, Amma was given a white sari after Appa’s death. I am not aware of how old this custom of a widow being required to wear a white sari is. I was twenty years old then—an ignorant village man with no knowledge of the outside world or any understanding of society. It never struck me that there was no need for a white sari.

In the next five years, there were several changes in the customs of our caste. Widows who were middle-aged or older were provided a saffron-coloured sari instead of a white one. The younger women were allowed ‘the red sari’—as coloured saris were known—or they were referred to as ‘dyed saris’. Today, not only are young widows allowed to wear a red sari but also it has become common for them to remarry. This is a huge change.

Since the white sari marked out a widow, Amma’s world shrunk considerably. In the mornings, she avoided stepping out of the house. She would leave home at five to supply milk to a few houses in the housing board nearby and return before the break of dawn, when the other milk suppliers were only starting their rounds.

People were mindful of omens when setting out in the morning for a festive occasion or other important work. Amma arranged her schedule so that she could avoid running into anyone and causing them bad luck. If people ran into her, someone might even say within her earshot, ‘A widow has come in front of us, let’s go back.’ If they dreamt about a woman clad in a white sari, they thought of her as Goddess Mariamman and rejoiced. But they didn’t approve of a woman in white appearing before them in person.

Also Read: “Poetry is my refuge”: Perumal Murugan

Amma only attended functions she could not afford to miss, and even then, she stood inconspicuously at the back of the gathering. Though it was she who was responsible for looking after our family, when my father was alive or after he passed away, Amma had no regrets about not getting the recognition due to her. Only when faced with financial difficulties did she lament: ‘Would I have to face this if that drunkard dog had been alive?’ But that was all.

The most pressing problem with the white sari was its maintenance. It was tough to work in the fields or to graze buffaloes and goats while wearing it. When being milked, the buffalo would swish its tail, sending drops of dung and urine flying on to her sari. Stains really showed up on a white sari, and it was difficult to get rid of them. Detergents that proclaimed, ‘Stains are good,’ were not available then. Amma initially struggled with the white sari, but from her own experience and based on her discussions with others, she learnt the art of maintaining it.

Amma had three kinds of saris. For functions, the weekly market and the annual temple festival, she wore a bright white. For supplying milk or walking only a couple of miles, she used one made of power loom coarse yarn. While working at home or in the fields, she wore the cheap material of dhotis or towels and used two pieces of these— one around her waist and another to cover the upper part of her body.

Amma neither expressed any yearning for coloured saris nor any frustration over not being able to wear them. When we talked about purchasing clothes for the family, she would say, ‘Am I going to wear colourful saris? Let’s just buy some white sari and not a very expensive one. How different can one white sari possibly be from another, and I only ever wear it on rare occasions.’ Though she would say this with a smile, I wasn’t able to bear it.

Also Read: Perumal Murugan: A Parable of our Times

Seeing how difficult it was to maintain a white sari, and how she felt about it, I once told her, ‘Enough, Amma. You have worn this sari all these days. From now on, wear coloured ones.’

Perhaps wondering if I was saying this just to see how she would react, she looked at me carefully.

‘I meant it, Amma.’

Now convinced, she said, ‘If that mouth had said this on the day I was given the white sari, I could have worn coloured saris. But if I start wearing them now, after wearing white all these years, it will only set tongues wagging.’

I did not have the courage to confront the deep anguish her words revealed. I hung my head in shame. If only my father had lived a little longer, I wished, or at least that I had gained some worldly wisdom when he died. ‘I lacked understanding then, Amma. Wear it now. Don’t bother about what the others might say. How long will they talk, ten days? Let them. Or a month? Let them. They will soon find something else to talk about.’

Amma refused. ‘I have worn it all these years. I am used to it. There’s no need to change it now.’